|

|

|

| |

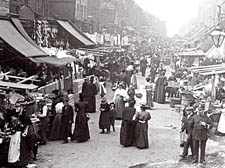

Chapel Market viewed from the east, circa 1898 Chapel Market viewed from the east, circa 1898 |

The Clerkenwell chronicles

Peter Gruner reviews a definitive history that took an editor and four writers eight years to complete

Order this book

THAT great campaigner for the poor Wat Tyler took his followers to Clerkenwell in 1381, as did the early trade unionists, the Tolpuddle martyrs, five centuries later.

The Chartists fought for political reform in clashes with police and Horse Guards on Clerkenwell Green in 1848.

Lenin plotted against his capitalist foes by printing his underground journal The Spark in 1903 opposite Clerkenwell Green, in a former Welsh school that was to become – and remains – the Marx Memorial Library.

And until the mid-1960s the communist daily newspaper the Morning Star was printed in nearby Farringdon Road.

Now two new hefty hardback volumes have been published – weighing in together at almost 10lbs – celebrating the history of the area, its buildings and its radical traditions going back to the 12th century.

The books, volumes 46 and 47 in the English Heritage Survey of London series, have taken four writers, a couple of illustrators and an editor eight years to complete, drawing on almost 20 years of in-depth research.

The two books combined, comprising 800 pages and 500 illustrations, are priced at £135 the pair, or £75 each. They may not be cheap, but these books are a definitive history of the area, and can be treasured by generations of readers.

Clerkenwell began in the Middle Ages as a settlement along the river Fleet, based around three religious communities.

Islington in the 17th century was the first independent village north of London. The high street was a busy halting point for travellers and traders on a medieval main route linking Hertfordshire and the North with the cattle market at Smithfield and the City.

At the same time, Clerkenwell had become a playground resort and spa, where people could escape London’s growing urban sprawl. Activities included sampling the alleged miracle mineral waters at Sadler’s Wells, and jolly blood sports such as bear and bull-baiting, cock-fighting and duck-hunting with dogs.

Britain’s famous dance theatre started out as an entertainment area for those visiting the spa. It was opened by vintner Edward Sadler in 1671. The waters, he declared, were of “extraordinary medicinal virtue”.

The fact that it later became an entertainments venue and still survives is remarkable, according to the chronicles.

Over more than three centuries Sadler’s Wells has lost more money than it has made, and on several occasions has come near to permanent closure and redevelopment, surviving periods as a skating rink and a warehouse, and one of prolonged dereliction.

By the mid-1880s Clerkenwell had a booming clock-making industry. Huge warehouses were built to house the trade. Household names like John Smith & Sons, makers of clock and watch glasses, had a three-storey factory in St John’s Square up until the 1980s. Thwaites & Reed, specialist in turret clocks, were in premises behind Bowling Green Lane until 1974.

But both these firms were forced to diversify because of cheap and clever foreign competition. By 1895 the crafting of handmade watches was considered dead and the Clerkenwell watch business survived mainly on repairs.

The printing trades fared better. Clerkenwell was the place to get your political manifesto – or in the case of the Salvation Army, General Booth’s War Cry – printed, often with no questions asked. Small printers occupied a third of the premises in 1939 and no less than half in 1946.

The Marx Memorial Library, where Lenin edited and printed his underground journal, was established 50 years after the philosopher’s death in 1933. A commemoration committee was set up through the Labour Research Department, Marxist publishers Martin Lawrence Ltd, and the trade union movement, with the aim of creating a permanent memorial.

Finsbury, the borough to which Clerkenwell once belonged, was the first in Britain to elect an Asian MP – Liberal Dadabhai Naoroji – in 1892. It became the most left- wing authority in the land, electing several communist councillors in the 1930s.

But, significantly, Finsbury appointed Georgian-born radical architect Berthold Lubetkin – famous for designing the penguin pool at London Zoo – to build the Finsbury Health Centre. Prior to the setting up of the NHS, it was the most sophisticated and modern in Britain, containing a TB clinic, foot and dental specialists, and even a solarium for the poor.

Novelist Peter Ackroyd pointed out at last Wednesday’s launch of the Chronicles at St John’s Gate in Clerkenwell that next month’s May Day march will start from Clerkenwell Green.

He added: “When you see the flags and banners swirling by, when you see the crowds moving this way and that, you will see the previous history of this place shining through the present.”

Mr Ackroyd, whose best-selling Clerkenwell Tales was published in 2002, said that in 1842 the then Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel banned all meetings on the green. The ban didn’t last for long.

“Meetings in favour of the Paris Commune met there and red flags were tied on the lampposts. Eleanor Marx and the Russian revolutionary, Kropotkin, addressed meetings on the green.

“Do the organisers of the May Day demonstrations of the 21st century know this history? Probably not.”

•

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|