|

|

|

| |

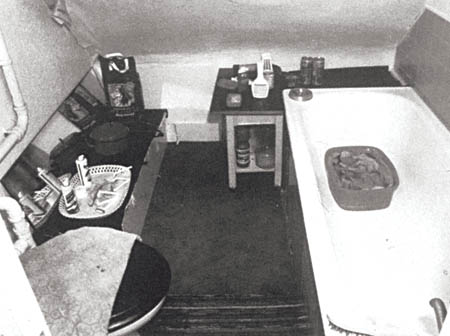

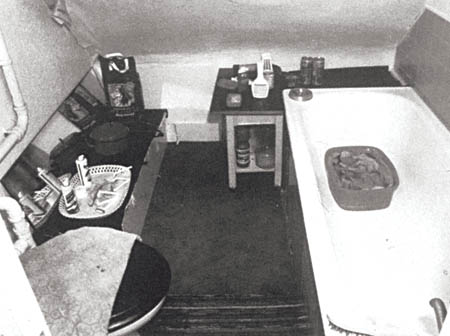

Dennis Nilsen attempted to dispose of remains in this bathroom’s drains |

Museum’s darkest secrets could see the light of day

From Dennis Nilsen to the Krays, macabre artefacts from the capital’s criminal past could be opened up to the public, writes Richard Osley

THIS is Orson Welles speaking from London,” the radio would blurt out in the early 1950s, before the chimes of Big Ben and a screeching violin cut through the airwaves.

And then Welles, with his smoky but authorative, wry voice, would introduce listeners to a “grim stone structure by the Thames” and extend an invitation to hear the stories locked inside.

This, he said, was the Black Museum, “a repository of death, a warehouse of homicide where everyday items have all been touched by... murder”.

It may all sound laboriously theatrical and the muffled recordings – still available on the internet – are quaint reminders of a bygone entertainment, but the inspiration behind those fireside tales was deadly serious.

The Black Museum, perhaps the most macabre collection of historical artefacts in the world, is not fiction. It still exists today, a real-life archive of Britain’s criminal past, a file for each murder from Jack The Ripper to Hawley Crippen, from Ruth Ellis to Dennis Nilsen. Curators through the years have delighted in telling stories of how ordinary objects, like TV aerials, can become murder weapons and earn their place in the museum. These are the actual weapons and evidence from scores of killings, kidnaps and robberies, stored in glass cabinets like relics at police headquarters at New Scotland Yard for more than 135 years.

Occasionally, misinformed guidebooks advise American tourists to stop at the Black Museum – officially known as the Crime Museum – when they visit London. But access is by invitation only and curators have been wary about letting in anybody that hasn’t made a written request first.

The museum has instead supposedly been used for training, showing rookie police officers the kind of real-life props they might find at crime scenes. Two severed arms sliced from a murderer convicted by the dirt beneath his fingernails have turned the stomachs of those who have been allowed in.

Special guests have included Arthur Conan Doyle, Harry Houdini and, bizarrely, Laurel and Hardy. Members of the Royal Family have also been among the few to see inside.

Now, several figures at City Hall believe it’s time to open parts of the museum to everybody.

London Mayor Boris Johnson told a recent budget committee meeting that he supports the idea and has given verbal approval for Brian Coleman, the Conservative London Assembly member for Camden and Barnet, to investigate the idea of opening a “Blue Light Museum” – an attraction which would in theory tell the history of all of the capital’s emergency services.

Mr Johnson described the resource as a “fantastic reservoir of cultural material” which could encourage young men and women to sign up to the police force.

The Mayor will have to tread carefully – he is dealing with objects straight from real-life crime scenes, death masks of executed killers and used nooses from abandoned gallows. Many relate to crimes that remain fresh in the public mind, such as those committed by The Kray twins and Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be hanged in Britain.

She was convicted for shooting David Blakely outside the Magdala pub in Hampstead, although there is still a campaign for the sentence to be commuted to manslaughter.

The exhibits also include the blood-stained police uniform that PC Keith Blakelock was wearing on the day he was killed in the Broadwater Farm riots in Tottenham.

Then there is the section devoted to Dennis Nilsen, the serial killer who murdered gay men at random before stashing their rotting bodies in cupboards and beneath his floorboards. Nilsen, who was working at the Kentish Town job centre by day and cruising gay bars for victims in the West End at night, was caught only when he called in plumbers to sort out a blockage in his bathroom – caused by the body parts he was hiding. He remains in jail, while parts of his kitchen and bathroom are in the Black Museum.

Crime writers who have seen inside are concerned that some of the museum’s exhibits might be too hard to stomach for the public.

Gordon Honeycombe, the former ITN newsreader who has written several books on the museum, including The Complete Murders of the Black Museum, says: “When you are walking around [the museum] there is a peculiar atmosphere. You see something like a screwdriver and it looks innocent enough, and then you find out that it has been used for some horrible murder.”

Now living in Australia, Mr Honeycombe adds: “There has been talk about opening up the Black Museum before, but they have always decided against it. They would have to think very carefully about what they would actually be putting on display.”

Martin Fido, a documentary-maker who wrote the Encyclopedia of Scotland Yard and now lectures in the United States, says: “Nobody ever forgets the severed arms in a big flask of formaldehyde, but they forcefully remind every policeman who sees them that you can fingerprint a corpse.

“Likewise, the cooking pot and cooker where the head of a Nilsen victim was found is a salutory reminder that anything may be used as a place of concealment.”

“There are some exhibits that aren’t obviously good pedagogic tools. The collection of hangman’s ropes, identifying which killed which murderer, might just as well be in Madame Tussaud’s chamber of horrors. The Victorian brothel contents are amusing, but not, I’d have thought, essential training tools.”

There have been attractions that have been designed to chill Londoners in the past, but Mr Coleman reckons their would be “queues around the block” if they opened the doors of the Black Museum.

For the first time in the capital’s history, he might get to see if his hunch is right. |

|

|

|

|

|