|

|

|

| |

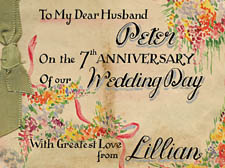

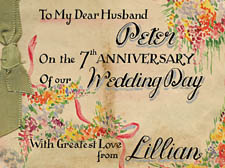

The wedding anniversary card was among the decorated letters Lillian sent her husband |

Dearest Heart

Letters and mementoes unearthed in a local studies archive tell a tale of wartime love, writes Dan Carrier

THE young woman pored over her work in semi-darkness, with just one table lamp shining a pool of light on her bureau.

She sat behind the blackout curtains of her West Hampstead flat in Priory Gardens, trying to ignore the muffled crumps of the bombs dropping across London. Lillian Hauselman’s painting style was careful, immaculate. She used her art as an escape as she desperately tried to keep her mind off the fate of her newly wedded husband. All she knew was he was not in England. He was doing his duty when his country came calling.

Lillian was not a trained artist, but she lovingly created highly decorated letters and cards for her much-missed husband. And while the story of Lillian and her husband Peter is not unusual, it is a touching, revealing illustration of one couple’s torment caused by conflict.

The collection of letters, cards, and mementoes from Peter’s time abroad came to light recently in a forgotten box in a store room at the Camden Local Studies Archive in Holborn. Historian Tudor Allen unearthed the collection and has created a new exhibition on the basis of the personal letters and mementoes. There were few clues as to when it was donated, but its content has revealed an intimate war time romance.

“We do not know much about the couple,” admits Tudor.

“It may have come to us via their family, we can’t be sure. But we can fill in some of the gaps of their story by looking at the materials we have. What emerges is they were very much in love.”

While little of the couple’s background is known, what is immediately apparent is the strain the pair were put under because of the war.

In the collection is a series of heart-aching letters written by Lillian. She was aware that her spouse was unable to tell her anything except to say he was alive: and even then, his letters could take months to arrive.

In the collection was an army template letter, laying out the bare facts of someone’s state of mind, and physical well being in a series of multiple choice boxes. It gave the soldier little chance to accidentally reveal something that may compromise security – but also meant loved ones were really no clearer as to the turmoil members of the forces must have gone through.

One of Lillian’s notes reads: “My darling Peter... just a line my sweet... hoping you are ok...”

Later, Lillian’s letters take a desperate tone.

“Please write soon,” she implores.

“I have been writing for a long time. Please look after yourself my darling. I love you very much. I am waiting for the day you come home...”

It would not be until May 1944 that he got back – and the box even contained a photograph taken by Peter as his ship moored in the Portsmouth docks.

Army records show that Peter was called up in the days before war was declared. He had been working as a car fitter and was taken on as a mechanic.

He served for a time in Northern France, though whether he was rescued from Dunkirk is not known. His service record does show he embarked on the troop ship SS Strathaird in November, 1941, from Portsmouth and sailed down the coast of Africa, stopping in Seirra Leone as he steamed towards South Africa.

He then reappears in Egypt in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. Montgomery’s Eighth Army was fighting Rommel’s Desert Rats across north Africa, and Peter’s work would have kept them on the go: the battlefield saw the first-ever large-scale motorised conflict and as a mechanic Peter would have played a vital role keeping the tanks and armoured cars running in such a harsh environment.

He saved a bill poster for a Cairo theatre during this posting. It advertises a show called George and Margaret, a love story set in Hampstead, which

must have made him yearn even more for his home.

We know their romance survived the war. The final clue the box contained was a baptism certificate for a little boy named John: it dates from 1946, and shows that once Peter had done his bit, he returned to his patient and loyal wife in West Hampstead where the pair finally started the family they must have been planning before the war so rudely interrupted them.

•

|

|

|

|

|

|