|

|

|

| |

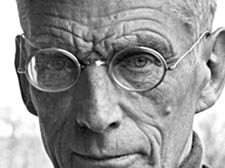

Beckett: not at all the hopeless teacher he claimed to be |

Sifting clues to the mind of a literary genius

Careful scrutiny of one of Beckett’s student’s old lecture notes offers an insight into the complex influences behind his work, writes Michael Worton

Beckett before Beckett: Samuel Beckett’s Lectures on French Literature. By Brigitte Le Juez. Translated by Ros Schwartz order this book

Beckett/Beckett. The classic study of a modern genius. By Vivian Mercier order this book

MOST famous for plays such as Waiting for Godot, Endgame and Happy Days, in which tramps philosophise about parsnips, aged parents live in rubbish bins, and a fadedly genteel lady sits buried to her waist in the sand endlessly deciphering the words on her toothbrush, Samuel Beckett has been described as one of the most pessimistic writers of modern times, yet his work also makes people laugh across the world.

In these two highly readable books we are given insights into the complexity of both the man and his works.

Le Juez’s Beckett before Beckett is like a literary detective novel.

Beckett taught courses on French literature at Trinity College Dublin from 1930-31, but his own lecture notes have been lost or destroyed.

Le Juez tracked down the notes taken by one of his students, Rachel Burrows, and uses these as the basis for reconstructing what he said. We learn that Beckett was not at all the hopeless teacher that he himself said he was. Indeed, there is clear evidence that he both enthused his students about French writers and gave them good practical advice on structuring their essays.

Le Juez points out that Burrows was, like many students, sometimes muddled in taking her notes, so she tenaciously follows up all of Burrows’s leads.

We learn, for instance, that Beckett hated Balzac for turning his characters into “clockwork cabbages” whose every action is determined by causality, much preferring writers such as Gide and Proust (and Dostoevsky), who highlighted the complexity of reality rather than trying to reduce it to explainable phenomena.

Le Juez’s book also emphasises Beckett’s admiration for the 17th-century French classical dramatist Racine, precisely for the lack of action in his plays. This does not mean that there is no psychological and emotional drama; on the contrary, and Beckett’s own work is influenced by Racine’s theory that “all invention consists in making something out of nothing”: as the Irish critic Vivian Mercier famously said, Waiting for Godot is “a play in which nothing happens, twice”.

Le Juez reveals, for example, that Beckett considered Act 2 of Racine’s Andromaque to be the finest act in all of classical theatre – because it reveals and anatomises the dynamics of the human mind, then its stasis and then the final catastrophe.

It is equally intriguing to learn that for him, Phèdre was the first of Racine’s plays to contain a “sense of sin”. Beckett before Beckett tells us a lot about the key French influences on him and his later literary development – and it encourages us to reconstruct the ideas in the lectures ourselves, comparing our own knowledge of Beckett’s works with the things he said about literature nearly 80 years ago.

Mercier’s Beckett/ Beckett was first published in 1977, but this highly personal book remains one of the key books on Beckett – and one of the most readable.

It is personal, quirky, sometimes irritatingly self-congratulatory, and occasionally strangely wayward in its interpretation of Beckett, as when Mercier attacks Beckett’s work for the proneness to self-pity expressed by his characters on behalf of the human race. Not particularly endowed with self-irony, he fails to understand that Beckett’s characters are endlessly fascinating because they need to be read as and through prisms of irony.

Where Mercier is particularly interesting is in the way in which he structures his book around a series of dialectical oppositions:

thesis/anti-thesis;

Ireland/the world;

gentleman/tramp; artist/philosopher; woman/man, etc.

Many critics have rightly indicated how much of Beckett’s thinking and writing is structured on a series of binary oppositions.

Here, he is very much working in the French philosophical tradition. However, most of Beckett’s critics focus on only one side of each of the oppositions, whereas Mercier emphasises the “minor” pole, eg the “gentleman” rather than “the tramp”, obliging us to rethink the nature of these oppositions and see them as complex, mobile relationships, rather than simple hierarchies.

One doesn’t always agree with Mercier, but he certainly makes one think and the book is written in such a lively fashion that it is difficult to put down – except in occasional moments of exasperation – and one quickly picks up the book again.

Both books will interest a wide readership, since they remind us in different but equally powerful ways that great literature comes in often labyrinthine ways from complex individuals who are themselves caught up in intricate webs of influence and resistance.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|