|

|

|

| |

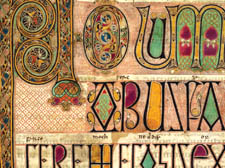

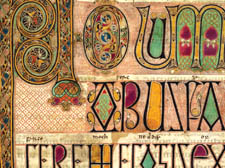

The Lindisfarne Gospels, currently held by the British Library, have become the subject of a campaign to return them to the North-east where they were created in the 8th century |

We’ve got their treasures and they want them back

A campaign to return some of the British Library’s rarest manuscripts back to the North-east is gaining momentum – and the battle is turning ugly, writes Richard Osley

THE British Library is losing friends in the North at an alarming rate, but to win them back some of its senior staff believe it would have to do the unthinkable and break up one of its most treasured and rarest collections.

The battle over what should happen to priceless manuscripts effectively amounting to one of Britain’s oldest bibles, the Lindisfarne Gospels, has turned ugly, risking a North-South divide. It has also lifted the lid on the private thoughts of those looking after the country’s historic treasures.

Some librarians privately believe that if the Gospels are returned to the region they were created in, as campaigners including MPs in the North-east demand, a dangerous precedent could be set.

After all, what if the rest of the country started asking for its locally significant items back?

Taken to its most ridiculous extreme, the British Library’s flagship building in King’s Cross could be emptied and its most cherished articles spread across the country.

In the words of one Library chief: “It’s regionalism gone mad.”

There has certainly been much fretting at the highest level in the boardroom and, kicking and screaming, the British Library has been brought to the negotiating table.

Nothing has been agreed, but in the past few weeks there have been the first suggestions that a relentless campaign – largely played out on the pages of the Newcastle Journal – to “bring the Gospels home” might one day be victorious.

The compromise would be to create a British Library unit in the North-east, probably near Durham University, which would allow librarians to continue looking after the priceless work. A recent visit to the North-east by Culture Minister Andy Burnham ended in a pledge to “certainly try to facilitate talks” on the issue.

In a PR battle, the Library has come off second best. The Journal used Freedom of Information rules to access a series of internal emails sent over the past five years which the British Library would surely have preferred to have kept private. In some of the discussions, the Gospels are referred to as “the baby”, and there are disparaging remarks about the ability of anybody other than the British Library to look after the scripts properly.

The Gospels were created by a monk on the Northumbrian island of Lindisfarne (now called Holy Island), in the early 8th century in honour of St Cuthbert and telling the stories of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The original cover was lost in a raid by the Vikings and the manuscript was later seized during Henry VIII’s reign. But its current condition is celebrated as being surprisingly well-maintained given its age. It is available to see at the Library and a computerised version is on its website, but campaigners including the Northumbrian Association, and the 160,000 who went to see them during a short loan eight years ago, maintain they are in the wrong place.

The emails uncovered by the Journal reveal the sharp-tongued criticism of the campaign among Library staff. The Dean of Durham, another character in the restitution row, is labelled “penny-pinching” with predictions that interest in a loan would die down when campaigners realised the cost associated with putting the Gospels on display for all. There are several references to how the issue has turned political. Both sides in the debate have sought government help but ministers have, until Mr Burnham’s recent visit, tried to stay out of the collision course.

In one internal email, it was suggested that Labour MP Roberta Blackman-Woods, one of the most vocal politicians in the campaign, would have to leave Northumbria and return to her native Northern Ireland if the principle of her campaign were to be agreed.

Oliver Urquhart-Irvine, Cultural Property Advisor at the British Library, said: “Objects can have a regional dimension, a national dimension and an international dimension. Not all objects have all three but the Lindisfarne Gospels unquestionably does.

“The (absurd) logical conclusion to the political argument is that Blackman-Woods goes back to Northern Ireland, the contents of all UK museums are emptied, etc, etc. Of course, restitution on political grounds is the opposite in effect to efforts at multi-culturalism in a multi-ethnic society.”

Other staff claimed losing the Gospels up north would “cut the heart out of the national collection... to remove it to the North-east would be a deprivation across the whole international Christian community.”

Language like “the natives are getting restless” and “we’re never going to change the hearts and minds of the North-east” has also been used in relation to the Gospels.

The emails also reveal suggestions to remind campaigners how many people visit the British Library every day and plans to try and fob off campaigners by offering other articles connected with the North-east for loan, rather than the Gospels. Such battleplans were never going to satisfy the lively appeal.

Questions have been asked in Parliament, private briefings have been arranged with top civil servants, but even with a compromise potentially in sight, the future of the Gospels remains unclear.

Ms Roberta-Blackman recently said she had noticed “a shifting in opinion” but her hope comes up against chairman of the British Library Board Sir Colin Lucas’s committed statement: “The Lindisfarne Gospels are of fundamental importance to a heritage that reaches far beyond the region in which the manuscript was produced.

“Visitors and scholars come to the British Library to view and study it as one of an unparalleled collection of devotional manuscripts which form the foundation literature both of Christianity and other great religions. The British Library Board would be seriously derelict in its obligation to provide access to these manuscripts for people of all faiths and nationalities if we allowed this collection to be broken up by removing one of its greatest treasures.”

|

|

|

|

|

|