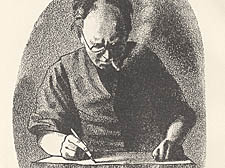

Self portrait |

Iconic designer who gave so much to art

Barnett Freedman was a important figure who deserves to be recognised, writes Sunita Rappai

HE was perhaps the finest lithographer of his time, a fiercely iconoclastic figure who later became an official war artist, a lecturer at the Royal College of Art and an artist with work in many major public collections, including the Tate.

So many in the art world were understandably shocked when a request to mark Barnett Freedman’s life with a blue plaque – he lived in Euston Road during the early part of his career – was turned down by English Heritage earlier this year.

David Gentleman, the renowned artist and water colourist, who lives in Gloucester Crescent, Camden Town, is one of a growing number of afficionados who feel that Freedman has been unfairly overlooked.

“He deserves a blue plaque because he was an important figure,” Gentleman says. “He was a very good and original artist whose work deserves to be remembered.

“He was never particularly avant-garde, he was in the English draughtsman tradition. A lot of his best things were commercial. His book jackets for Faber are classics and he did admirable illustrations – the wonderful series of stamps for the Silver Jubilee for example.

For many, Freedman, who died in 1958 aged 57, remains best known for his iconic book jackets and illustrations – including works such as Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, War and Peace and Wuthering Heights.

But he was also a superb lithographer and graphic artist, much in demand for commercial and industrial graphic design for companies including Shell and BP, and as a stamp designer for the Post Office – something that Gentleman understands well.

And despite relative public obscurity, he was always well regarded by other artists. Gentleman actually knew Freedman through his parents as a child growing up in Hertford, and later, when their paths crossed at the Royal College of Art.

“My father was an artist and designer and had known Barnett professionally,” he says. “They knew one another quite well. I saw him enough for me to be embarrassed later on when I was in my 20s and teaching at the Royal College briefly and trying to keep my modesty. Barnett would say: ‘I dangled him on my knee.’

“He influenced me in the sense of his meticulous workmanship. He was a real master of it. He might not have been a popular or widely recognised man by the ignorant but anyone who knew anything about graphics would have thought highly of him. I admired his work a great deal.”

Professor Ian Rogerson, a retired book historian from Manchester Metropolitan University who has compiled a book on Freedman’s best work to be published later this year, agrees.

Rogerson’s book, simply entitled The Graphic Work of Barnett Freedman, is a lovingly assembled, lavishly printed homage to an artist he calls “the world’s best auto-lithographer.

“I find that even after looking at his illustrations for some 50 years, I get more and more pleasure from the colour in his work,” he explains.

“He did some absolutely marvellous book illustrations between 1930 and 1951. He was a wonderful lithographer, very well known in London art circles. He was also a very good letterer – he did a lot of lettering.

According to Rogerson, Freedman’s legendary bark – even Gentleman describes him as “quite prickly and alarming at times” – was also a lot worse than his bite. “He was a fiery individual who did not respond kindly to discipline and was always at war with the civil servants,” Rogerson says.

“I know people who were taught by him who say he was a very careful and punctilious teacher who paid a lot of attention to his students – but he could fire off if he was angry.

“At heart, I think he pretended to be a harsh kind of person, but he was very good to a lot of people.”

Freedman the iconoclast, the cockney who never strayed far from his East End Jewish roots, the Royal College-educated-artist who loathed pomp and ceremony would probably have smiled wryly at all the fuss. But for many, official recognition of Barnett Freedman is long overdue.

Rogerson says: “A lot of people who do not seem to have contributed as much to the arts have managed to get blue plaques. Freedman’s work is being increasingly collected – and he is being recognised more and more as a major contributor to British art.”

CLICK BELOW TO SEARCH FOR ACCOMODATION

|