Poussin's Plague of Ashdod depicting the Old Testament theme of plague

Poussin's Plague of Ashdod depicting the Old Testament theme of plague

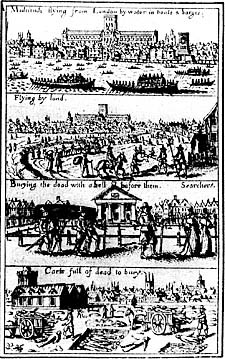

A woodcut of unknown origin showing the flight from London

A woodcut of unknown origin showing the flight from London |

A plague on you, sir

For centuries plague was a feared fact of life. Lord Nicolas Rea explores the macabre history of life with death

London's Plague years

By Stephen Potter Tempus Publishing £17.99

It is generally known that there was a terrible epidemic with high mortality –

the ‘Black Death’ – that afflicted Europe during the middle ages.

The Great Plague is often mistakenly thought to be another name for the same epidemic.

In fact the ‘Black Death’ reached Britain in about 1348, and ‘The Great Plague’, the last outbreak in this country, struck much later, in 1665, the year before The Great Fire of London.

Plague is a bacterial infection caused by the bacillus Pasteurella pestis, after Louis Pasteur, but now renamed Yersinia pestis after Dr Alexander Yersin who finally uncovered the cause and mode of transmission of the disease in 1894. During the whole time the epidemic was prevalent in Europe the cause was unknown.

Stephen Potter’s scholarly but very readable and attractively produced account of the successive waves of plague that swept across the old world during the last millennium brings it all into focus.

As a historian with special knowledge of London and England in the 16th and 17th centuries he narrows that focus down to the cause and effects of plague on London, often down to a very local level and relates it, not without humour, to the historical events of the time

It is generally known that there was a terrible epidemic with high mortality – the ‘Black Death’ – that afflicted Europe during the middle ages. The Great Plague is often mistakenly thought to be another name for the same epidemic.

In fact the ‘Black Death’ reached Britain in about 1348, and ‘The Great Plague’, the last outbreak in this country, struck much later, in 1665, the year before The Great Fire of London.

Plague is a bacterial infection caused by the bacillus Pasteurella pestis, after Louis Pasteur, but now renamed Yersinia pestis after Dr Alexander Yersin who finally uncovered the cause and mode of transmission of the disease in 1894. During the whole time the epidemic was prevalent in Europe the cause was unknown.

Stephen Potter’s scholarly but very readable and attractively produced account of the successive waves of plague that swept across the old world during the last millennium brings it all into focus.

As a historian with special knowledge of London and England in the 16th and 17th centuries he narrows that focus down to the cause and effects of plague on London, often down to a very local level and relates it, not without humour, to the historical events of the time.

These included the reformation, the accession and reigns of the Tudors and the early Stuarts, the civil war and the lifetime of William Shakespeare, to whom it was familiar: “A plague o’ both your houses” (Mercutio as he receives a mortal stab from Tybald in Romeo and Juliet), is his best-known use of the word but it appears several other times in the complete works.

In 1517 Henry VIII moved his entire court out of London, first to Windsor and then to a place unknown further into the countryside to escape the outbreak of plague in 1517, and did not return until long after the outbreak had subsided.

This resulted in a failure to keep Christmas and “general discontent” among the poorer people who had remained and bore the brunt of the epidemic – a medieval precedent for New Orleans? – Cardinal Wolsey, the Lord Chancellor, ordered the city authorities to seek out those who uttered “seditious words” against the King.

Potter brings the whole era vividly to life with verbatim accounts by people who lived through the macabre experience and includes 87 contemporary maps and engravings by Hans Holbein and others illustrating life and death in London and Holland during the plague years.

He gives us a simple but accurate description of the bacteriology and epidemiology of the disease (bubonic plague) as well as other epidemics, one known as the “swetying sycknes” with a high fever and high mortality which may have been a virulent form of influenza, and shows how plague waxed and waned, taking its natural course over time since there was no known cure and public health measures were ineffective because its mode of spread was not understood. However, although some theories as to its cause were very far fetched, the idea of contagion and infection was widely held, leading to efforts to isolate cases and the houses in which they occurred, but to little avail since the rats and their fleas which carried the disease were free to move as they wished.

Some Italian city states operated a public health policy based on the supposition that the disease was spread from person to person, by excluding travellers from areas where plague was prevalent from their city for 40 (quaranta in Italian) days – hence quarantine – with some success. However, a widely held view was that it was a manifestation of God’s anger (a view sometimes expressed by religious fundamentalists to explain the origin of Aids/HIV): “Behold, with a great plague will the Lord smite thy people, and thy wives, and all thy goods” and that atonement and repentance of sins was the only answer, and many disobeyed control orders.

This is probably the most detailed and accurate historical account of the impact of plague on London that has been written. But also, like Albert Camus’s The Plague, an allegorical account of an imaginary plague in Oran, Algeria, it captures and transmits the frustration and anguish of ordinary people and those who governed them in the face of a relentless but invisible enemy.

|