Wanda Barford’s latest collection tries to put the

pain behind her |

Wanda's odes to love and passion

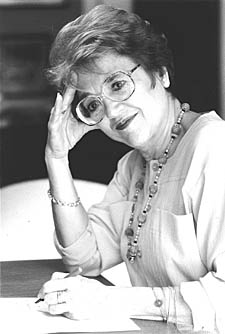

Wanda Barford proves that it's never too late for passion in love or writing, says Ruth Gorb

What is the Purpose of Your Visit

by Wanda Barford

Flambard Press, £7.50 order this book

AT the age of 75, the poet Wanda Barford has written a series

of love sonnets that move, delight and stir the blood. Demurely

she says that she hopes that one of them “5am,” is

not pornographic. Certainly it is passionate – “well,

I’m a passionate person,” she says – and with

others under the title Singing Like a Woman in Love puts paid

once and for all to the idea that sexual love is the prerogative

of the young.

The sonnets are part of her latest collection of poetry, What

is the Purpose of Your Visit? The title, and the picture of

the train on the cover evoke emotions other than of love –

rather of fear and displacement. Barford sees the train as a

symbol of the fractured, restless 20th century. “It was

filled with so much pain – not that this one is starting

so well,” she says.

Her desire to put all the pain behind her sees the book beginning

with poems under the heading Goodbye 20th Century.

They are about disrupted lives and disrupted childhoods like

Wanda Barford’s own. Hers started well enough. She was

born in Milan to Jewish parents, her mother from the island

of Rhodes and her father from Turkey, and the family lived in

considerable luxury – there are memories of a sunken pink

marble bath, of driving in a Lancia, one of the earliest motor

cars in Milan.

Mussolini had come to power in 1922 and at first he seemed like

good news. Then it all changed. “You killed Christ,” said one of the maids to the child Wanda.

Fearful, the family left Milan. They joined other refugees in

the cafés of Paris where the talk was all of the safe

places to run to, with maps of the world spread on the tables.

Wanda and her parents made for Rhodesia where they stayed for

17 years. It was safe, but it stifled the cosmopolitan souls

of Wanda and her mother.

“As soon as my father died, my mother upped and went to

live in Paris,” she says. “I came to London, where

it was wonderful to have everyone asking, ‘When are you

getting engaged?’ I was in the country of Dickens. I fell

in love with London, and I’ve been in love with it ever

since.”

She lives, as she has for many years, in the heart of Belsize

Village.

Her training was as a musician, as was her first career: she

taught piano at New End School, and at South Hampstead School

for Girls, where both her daughters were pupils. Than in 1990,

her life changed. She had been suffering from bouts of depression,

so badly that she remembers looking up at a tree one black day

and considering which branch to hang herself from.

She recalls: “Then I had my 65th birthday.

“I got my freedom pass. I stopped teaching. I decided it

was now or never. I was going to write. I had so much stuff

I wanted to get rid of, stuff that was festering inside me and

had been for years.”

She started to write poetry. It poured out of her, the pain

she had tried to suppress, the pain of the members of her family,

including her grandfather, who had died in Auschwitz – “I felt I owed it to them to remember them” she says.

Barford published her first volume of poems, Sweet Wine and

Bitter Herbs, and it was well received.

The depression gradually lifted, and when she had a major operation

in 2001 she remembers thinking: “At least I’ve written

that; I can die peacefully.”

Far from dying, she appears to have been re-born. Youthful and

elegant, full of zest and intellectual energy, she has become

part of the literary establishment. Her poetry is highly regarded,

although she says she is still learning and regularly attends

a poetry workshop at Morley College.

As she grows older, she finds that her Jewishness has become

more important to her.

One sequence in her new collection was inspired by a study tour

of Israel she made in 2000 with the Council of Christians and

Jews.

And she sees that growing awareness of her roots affected her

long-standing marriage to a non-Jew. “It was when I was

writing my first poems, about my family,” she says. “He

said: ‘You are not Holocausting again, are you?’ It

was like a stab in the heart.

The marriage was, she says, sometimes bad, sometimes good. Her

husband died in 1997, and no, the love poems are not written

about him. She has now, she says, “a very good friend”.

It is he who has inspired the sequence she calls Celebrating

Love in Old Age, poems filled with tenderness and mature self-awareness.

“At an age as

ridiculous as ours –

The curving spine, the sagging skin…

Yet love there was,

As vigorous and strange

As any younger love might be

And maybe twice as loyal

For all the

knowledge of deep hurt,

For the life already lived.”

The sense of the ridiculous is always there, and an impish sense

of humour. Poems towards the end of her book make sly fun of

contemporary attitudes, health fears, the impossibility of filling

in forms – is she Caucasian, Semetic, White, Other…?

She wonders.

She writes all the time; there are scribbles, she says, all

over the house. What inspires her? She gives the answer in a

poem: All she needs, she says, is her pen, old diaries, light.

Most of all she needs her heart “with its accumulated baggage…forever

on the edge of something radiant, to take me to the stars and

back.”

|