Books: The London Nobody Knows. By Geoffrey Fletcher.

Published: 15 September 2011

by DAN CARRIER

A DISH of jellied eels sounds like a Music Hall joke nowadays – yet the dish once played a major role in the diet of so many.

In Camden Town, there is one remaining cafe still serving up the delicacy – Castles, in Royal College Street.

It was not always like this. In the 1960s, writer and illustrator Geoffrey Fletcher noted that eels were very much available.

The graduate from the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art had a job penning and illustrating a column for the Daily Telegraph.

It was about London, providing the upper-class readership with an insight into the dirty old metropolis from the safe haven of their breakfast tables.

In 1962, the year he started work at the Telegraph, Fletcher produced a book called The London Nobody Knows – a guide to “the tawdry, extravagant and eccentric”.

It was later made into a film, narrated by James Mason, and was a mixture of Fletcher’s ability to use words to paint pictures of a city that has all but disappeared.

It is from the pages of his book that you can discover quite how much the diners of Camden Town loved an eel.

“Jellied eels were a staple diet in Camden Town and still are, though the best of the jellied-eel establishments have since disappeared,” he writes in a chapter focusing on Camden Town. “Eel-pie saloons appear to date from the turn of the century...”

He describes “abnormally vigorous infants drinking Tizer, lorry drivers and old, shuffling men with cloth caps. The menu includes hot meat pies on thick plates or you can have pies with mash. This is served with helping of a livid pale liquid of unearthly appearance...”

The book, re-published this month, covers Camden, Islington, the East End and various places in between. Fletcher had a burning passion for the London that was rapidly disappearing, and singles Camden Town out for particular consideration.

He writes: “It is no wonder that Sickert found so much material in Camden Town – those dolorous bed-sitters, the damp basement flats where life, seen through lace curtains, is a succession of human feet wearing out the pavement tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.”

Historian Dan Cruickshank, who has written a foreword to the re-issue, says Fletcher was a strange mix: someone who clearly cherished London’s streets, shops and people, and bemoaned the ever-onward march of modernism that was sweeping away the remnants of Victorian and Edwardian, pre-war London – but he wasn’t a campaigning conservationist like his friend John Betjeman.

“Fletcher wanted to record things before they disappeared,” says Cruickshank.

“He regrets their demise but does not do anything about it.

“It is a splendidly evocative book that offers a window on a world of 50 years ago. The book records not only London buildings that have gone but also lost ways of life, and is full of things that are otherwise undocumented.”

Part of the joy of Fletcher’s book isn’t just his eye for the weird and wonderful, it is the descriptions accompanying his illustrations.

He describes how, even before supermarkets got their paws on our purses, London’s markets had changed.

“While I like the bilious jars of pickles and the weary teddy boys, I cannot help regretting the fact that London markets are not what they were,” he writes after strolling through Chapel Market.

“I miss the quacks, for example – particularly those who sported a plaster cast of a foot crippled with bunions and the medicine men who displayed testimonials from the crowned heads of Europe.”

He speaks of the stalls’ “rich colour: the blue-pink of plucked chicken, partridges and pheasants touched with dull reds and Prussian blue and occasionally a black and white hare; and then the fish stalls, largely of pearly white from the underbellies of plaice and cod, colour accents being supplied by parsley...”

Looking back at Fletcher’s works today, it is clear he was an architectural soothsayer who could see that post-war Britain, while in need of improvement, was also in danger of losing the background that told the stories of the city’s evolution.

He speaks of the Horse Tunnels in Chalk Farm Road, then falling into disrepair: “Glistening damp steals down walls,” he writes. “Going through the passages... is an uncanny experience, like walking into a drawing by Piranesi.”

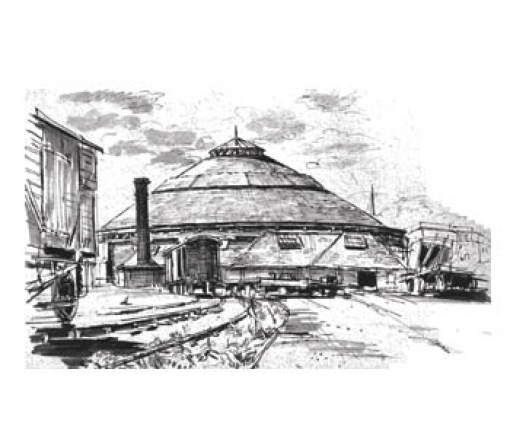

Landmarks like the Horse Tunnels and the Roundhouse are open again, but not, of course, for their original use.

The Horse Tunnels make up the new, massive Camden markets, and are used to sell clothes and knick-knacks. The Roundhouse is a concert venue: from industrial transport, through decay, to shiny retail.

It is a statement of truth about the changing nature of Britain’s wealth creation. Our forefath5ers built things and moved them about on the transport system that British engineers invented.

Now it’s entertainment and shopping.

• The London Nobody Knows. By Geoffrey Fletcher. Foreword by Dan Cruickshank. The History Press £9.99.

Comments

Post new comment