Books: Review - Holloway Prison: An Inside Story by Hilary Beauchamp

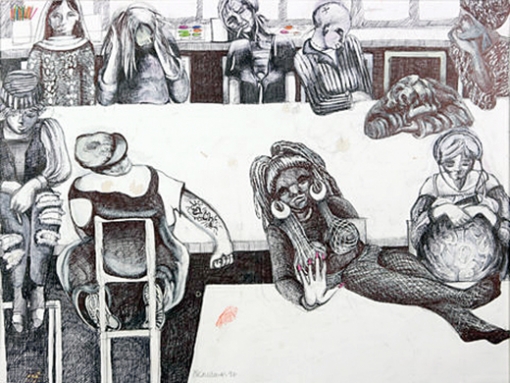

After 30 years’ teaching women inmates, Hilary Beauchamp’s inside story of art behind bars exposes a dark world of desperation, writes Peter Gruner

Published: 10 June, 2010

AWARD-winning art teacher Hilary Beauchamp felt “duty bound” to resign from her job teaching art at Holloway prison in March this year before publishing her disturbing new book about life for women behind bars.

One can see why. Much of what she reveals in Holloway Prison: An Inside Story, based on 30 years’ teaching at the Victorian-built institution, will not be welcomed by the authorities. Prison officials don’t like the spotlight turned on methods which might appear cold and uncaring and have so far chosen not to comment on the book.

The work, however, does have some lighter moments, such as when 30 bored and indifferent prisoners all decided one day to join Ms Beauchamp’s art classes. The authorities suspected something was up and they were right.

The women were not interested in painting at all, but had heard that Ms Beauchamp was giving away free tobacco.

What she had done was “unforgivable” in penal terms. “I had genuinely felt sorry for the poverty-stricken inmates who claimed that they couldn’t afford the price of a packet of Golden Virginia, so I gave them tobacco” she says. “However, it was strictly against the rules. You don’t give anything away in prison.”

Ms Beauchamp earned an MBE for her prison work. She also won the coveted ITV Teacher of the Year in 2007 after the prisoners all voted for her. The book devotes her artist’s eye to life in Britain’s most famous (or infamous) women’s prison. “To begin with there’s the noise,” she says. “No one ever talks in prison. They shout. It’s a relentless din at all times without a break.”

Many women prisoners suffer from depression and low self-esteem. To escape they succumb to “prison sloth”. Ms Beauchamp writes of “cells of hibernating bodies, parcelled up in blankets, sleeping their days away. Half alive, they’d queue up at medicine time and beg for various pills to render themselves comatose”.

Teaching for such a long time, Ms Beauchamp got to know many prisoners individually, such as Mona, who was convinced she was being visited by the ghost of Ruth Ellis, the last woman in the UK to be hanged. “Poor Mona never seemed to sleep,” Ms Beauchamp writes. “One hand gripped her rosary and the other hugged her Bible.”

Most of the women in prison seem to be sick and on some kind of medication. Epileptic fits are frequent events, as are asthma attacks. Ailments aggravated by years of drug or alcohol abuse.

“Women who couldn’t spell birthday could write the name of medications,” Ms Beauchamp writes. “Four and five-syllable medication terms rolled off their tongues.”

Anger and violence is always bubbling under the surface in Holloway. One prisoner, “Tango”, had a reputation as a bully. “I’d seen her temper,” Ms Beauchamp writes. “She was a worry when she was being nice but she was also a worry when she was fierce. She could rip out a toilet from its plumbing, throw beds, tables and go several rounds with the strongest male officer.”

With new prison governors came new regimes. One governor downgraded art to the point that classes became a rarity, while another upgraded them again. A popular mural of a rainforest, lovingly painted by the inmates in the Mother and Baby wing, was suddenly removed despite the efforts of the architect and designer Sir Hugh Casson, a friend of the prison, who Ms Beauchamp had alerted at the last moment.

Theatrical performances and fashion shows are very popular inside, but they were often more for the benefit of the guests and the artists than the prisoners themselves.

Ms Beauchamp writes how 80 women were employed to create a colourful backdrop for one fashion show, only for the outside director to reject the work at the last moment, creating huge disappointment.

At the end of her book Ms Beauchamp laments that she couldn’t do more to inspire the women but also chastises the education authorities in prison for wanting to see everything in terms of profit.

She says: “We learned to tick the boxes, whilst the more worthwhile things we tried to do, but which didn’t count, went unrecognised, making nonsense of our professional lives. So the job became somehow fraudulent, a ‘con’, sterile and soulless.”

However, she admits that conditions in Holloway have improved a lot since she first began working there.

After reading this book one is reminded of comments by Joan Bakewell. In 2006 she called for the majority of women prisoners to be released from Holloway on the premise that most of them were not violent criminals and needed emotional support or psychological help rather than detention.

• Holloway Prison: An Inside Story. By Hilary Beauchamp. Waterside Press, £22