John Gulliver - We recognise the hand that slapped the table

Published: 28 July 2011

WHEN Rupert Murdoch’s hand slapped the table during the parliamentary grilling last week, millions of TV viewers saw it.

But only a few saw the media baron in action when he met a group of trade unionists in the mid-1980s just before he closed down his newspapers, moved them secretly into his Wapping fortress – and sacked 5,000 workers.

The memory is lodged in the mind of Camden Council’s deputy leader, Sue Vincent, because her father Vic sat opposite him and witnessed an amazing scene.

Vic, a trade union shop steward at the Sunday Times office in Gray’s Inn Road, was part of a deputation that had arranged to meet the great man.

For 45 minutes they sat and waited, and then in walked Murdoch – much younger than he is today, of course, full of a sense of power, an owner of the tabloid the Sun as well as The Times and Sunday Times newspapers.

“What do you want?” he asked the deputation.

It was obviously the opening gambit of a man who wanted to shake down his enemies. Vic explained that they wanted to discuss their long term grievance, the need to negotiate their “terms and conditions”.

As he said this, he showed Murdoch their contract. Murdoch glanced at it, took it from his hand – and then to everyone’s astonishment – slowly tore it up.

He didn’t say a word. Then Murdoch walked out of the room. For him, that was the end of the evening.

Shortly afterwards, Murdoch demonstrated his feelings again by sacking all his workers and offering new contracts to those who wanted to work at his new Wapping plant, which he had secretly built.

This moment of high drama loomed large in Sue’s mind as she told me about her father, who died early last year at the age of 80.

“He was a lovely man who would light up a room,” she told me.

Born into a working class family off the Old Kent Road, the family lived in an old house, later condemned. It had no running hot water – a tin bath was kept in the kitchen for the family bath.

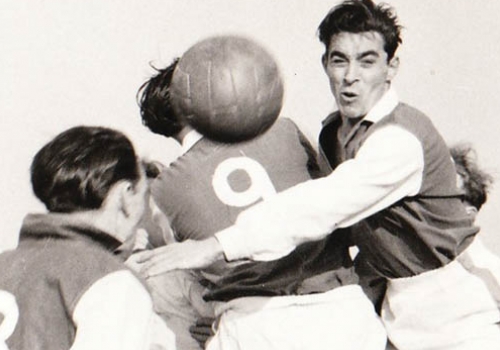

Typically, Vic played out in the evenings in those far off days in the 1930s and 1940s, and even starred as a boxer and footballer. He almost turned pro as a featherweight, and later went for trials for Fulham and Chelsea football clubs.

But he settled for a job as a printer and worked first as a typesetter and later a “machine minder” on the big presses at Odhams in Long Acre in Covent Garden, where the Daily Herald and later the Sun were printed.

Inevitably, he became one of the 5,000 men sacked by Murdoch. Both he and Sue’s mother Marian marched and protested outside the Wapping plant. But, like so many of those sacked, his life was turned upside down. Sacked in your fifties! What do you do? And like a few old printers, Vic became a cabbie.

His life would never be the same again. The old camaraderie of the print room was gone – the life of 30-40 years – all gone, the moment Murdoch tore up that contract.

But Vic wanted his daughter to understand the need for respect that ordinary people are entitled to – and when she was only 13 he suggested she should read the classic socialist novel by Robert Tressell, the Ragged Trousered Philanthropist.

The hands that tore up that contract were the same hands that slapped the table last week.

They were gnarled with rivulets of veins and Murdoch’s face had aged. But it was the same old Murdoch, I believe, with the same contempt for human beings.

I would have liked to have met Sue’s father and had a drink with him.

Murdoch? Never!